The history of literature is also the history of change. Genres, those recognizable categories that once neatly organized the world of storytelling—tragedy, comedy, romance, epic—have never been static. They evolve alongside societies, technologies, and ideologies. Yet no period has questioned and reshaped literary form as profoundly as the postmodern era. Emerging in the mid-20th century and continuing to shape 21st-century writing, postmodernism disrupted the boundaries of narrative, authorship, and truth. Genres that once defined literary order now coexist in hybrid forms, reflecting the chaos and complexity of modern existence.

Postmodern literature challenges the very notion of “pure” genre. It is a space of paradoxes: irony and sincerity, reality and simulation, fragmentation and wholeness. In this world, the detective novel becomes metafiction, the historical epic becomes parody, and the romantic narrative becomes a reflection on its own impossibility. Understanding how genres adapt and transform under postmodern conditions is crucial not only for literary scholars but also for writers and readers navigating today’s cultural landscape.

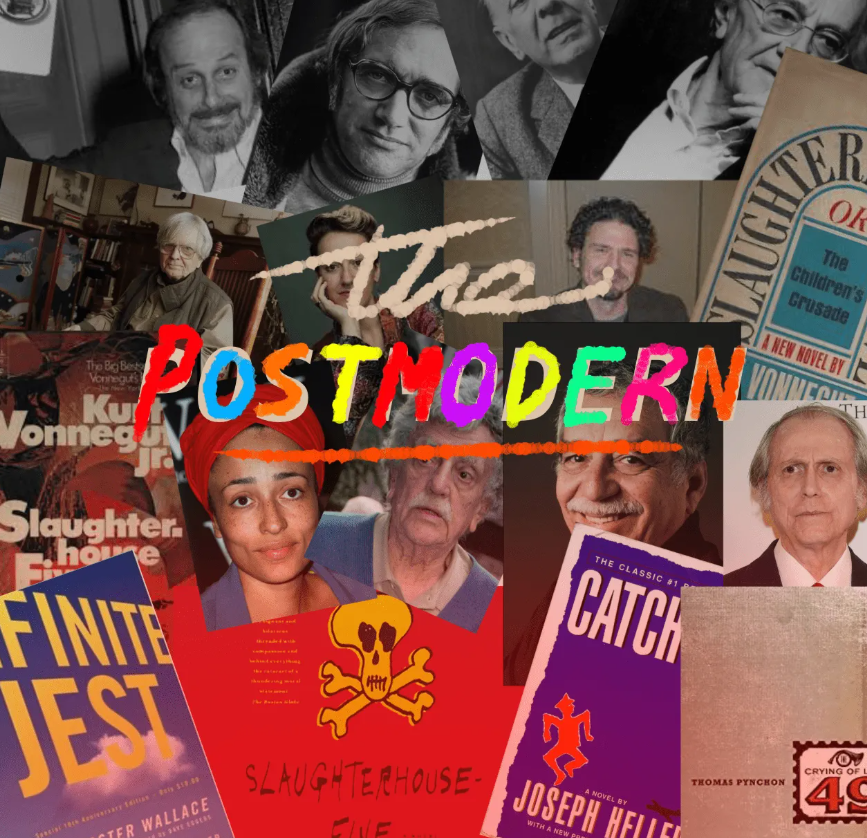

The Collapse of Boundaries: Postmodernism as a Genre-Defying Force

To understand genre transformation in postmodernism, one must first grasp the movement’s central philosophy. Postmodernism arose after the devastations of World War II and the disillusionment with grand narratives—religious, political, and cultural. As theorist Jean-François Lyotard famously stated, postmodernism is defined by an “incredulity toward metanarratives.” In literature, this meant that writers no longer trusted universal truths or stable meanings.

Instead, postmodern authors embraced fragmentation, intertextuality, irony, and play. They questioned not only what stories could be told but also how they could be told. Genres, once containers of meaning, became tools for deconstruction.

Consider Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973) or Don DeLillo’s White Noise (1985): both mix elements of satire, science fiction, espionage thriller, and philosophical treatise. Similarly, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) merges dystopian fiction, political allegory, and feminist critique. Postmodern writers don’t discard genres—they layer them, blurring distinctions until readers must navigate uncertainty as part of the aesthetic experience.

Even realism, once considered the most “truthful” genre, becomes suspect. In Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler (1979), the reader is both protagonist and participant, the novel both text and commentary on the act of reading. Genre, in postmodernism, no longer dictates form—it becomes a subject of exploration.

Hybridization and Metafiction: The New Face of Genre

One of the most distinctive features of postmodern literature is its hybridization—the blending of multiple genres and media to produce new forms of expression. Where classical literature valued unity, postmodernism celebrates contradiction.

For example, Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five (1969) fuses historical fiction with science fiction and memoir, undermining any single interpretation of truth. Similarly, Jeanette Winterson’s The Passion (1987) combines magical realism, historical narrative, and gender commentary, refusing to settle into one mode of storytelling.

The rise of metafiction—fiction that reflects on its own creation—has further transformed genre conventions. Works such as John Fowles’ The French Lieutenant’s Woman (1969) parody Victorian romance while exposing the manipulative power of narration. By doing so, they highlight the artificiality of genre expectations themselves.

Postmodern literature also engages with popular and “low” genres that traditional academia once dismissed. Detective fiction, horror, pulp adventure, and comic books become serious artistic tools. Authors like Umberto Eco (The Name of the Rose) and Neil Gaiman (American Gods) use genre conventions to question systems of belief and knowledge.

This blending of “high” and “low” culture signals a democratic shift: in the postmodern world, all narratives—whether myth, commercial fiction, or avant-garde experiment—occupy the same cultural playing field.

| Traditional Genre | Postmodern Adaptation | Representative Work / Author |

|---|---|---|

| Historical Novel | Reimagined as metafiction and alternate history | The French Lieutenant’s Woman – John Fowles |

| Detective Fiction | Self-reflexive mystery questioning truth itself | The Name of the Rose – Umberto Eco |

| Science Fiction | Dystopian allegory and philosophical speculation | Snow Crash – Neal Stephenson |

| Romantic Narrative | Fragmented love story emphasizing perception | Written on the Body – Jeanette Winterson |

| Epic / Myth | Urban mythology and cultural synthesis | American Gods – Neil Gaiman |

| Realism | Ironized, self-conscious commentary on narration | White Noise – Don DeLillo |

Technology, Media, and the Digital Expansion of Genre

Postmodernism thrives in a media-saturated world, and the digital revolution has amplified its reach. The internet, interactive fiction, and transmedia storytelling have created entirely new narrative ecosystems where genre boundaries dissolve even further.

Online platforms like Wattpad, Archive of Our Own, and interactive storytelling apps allow writers to remix genres in real time, responding to audiences as they write. The rise of fanfiction, often blending fantasy with realism or romance with political commentary, continues the postmodern tradition of intertextual play.

Similarly, digital literature and video games blur the line between author and player, fiction and participation. Works like Gone Home or Disco Elysium embody postmodern hybridity in new media: combining narrative depth, philosophical inquiry, and emotional realism in interactive environments.

The influence of hypertext theory (George Landow, 1990s) predicted this shift—stories as networks of meaning rather than linear paths. Today, AI-assisted writing tools and virtual reality environments allow authors to construct multidimensional texts, echoing postmodernism’s fascination with multiplicity.

In this landscape, genre becomes a living organism, adapting to technology, audience expectation, and cultural context. The postmodern spirit survives not only in print but across screens, pixels, and digital voices.

From Fragmentation to Fluidity: What Comes After Postmodernism?

As we move deeper into the 21st century, critics often ask whether postmodernism has ended—or whether it has simply become the default mode of cultural production. Many argue that contemporary writing has entered a post-postmodern phase, characterized by a renewed search for sincerity, empathy, and connection. Yet the legacy of postmodern genre transformation remains.

Authors like Ali Smith, David Mitchell, and Jennifer Egan continue to weave multiple genres into their narratives, but they do so with emotional depth that transcends irony. Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad (2010), which includes a PowerPoint chapter, embodies formal experimentation without sacrificing humanity. Similarly, Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas (2004) uses six nested genres—diary, thriller, dystopia, science fiction—to show how stories echo across time.

This evolution suggests that postmodernism has not destroyed genre; it has freed it. Writers now see genre as a toolkit, not a constraint—a means to express the layered realities of globalized, digitized life.

Moreover, readers have adapted as well. Contemporary audiences are comfortable navigating hybrid forms, expecting novels to shift tones, styles, and perspectives. The success of cross-genre works like The Hunger Games (dystopia + political allegory + romance) or The Road (post-apocalyptic fiction + moral parable) shows that the postmodern reader craves both narrative complexity and emotional authenticity.

In this sense, the transformation of genres in the postmodern era mirrors the transformation of humanity itself: from rigid systems to fluid identities, from certainty to exploration, from singular truth to a chorus of possibilities.

Conclusion

The postmodern era revolutionized not only how literature is written, but how it is understood. By dismantling the strict boundaries of genre, it opened space for innovation, dialogue, and inclusivity. The detective novel became a philosophical labyrinth; the romance, an experiment in selfhood; the epic, a reflection of collective myth in a globalized world.

Genres no longer function as boxes—they function as maps, guiding both writers and readers through an ever-shifting cultural landscape. Their transformations remind us that art evolves not through obedience to rules but through courageous re-imagination.

As technology continues to blur media lines, and as global voices reshape the literary canon, the future of genre promises to be even more fluid, inclusive, and unpredictable. The postmodern legacy is one of freedom—the freedom to combine, subvert, and reinvent.

Ultimately, literature in the postmodern age teaches us a vital truth: that storytelling, like humanity itself, thrives not on certainty but on endless reinvention.